The NES game “Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out” uses a password system to allow players to continue from certain points in the game. Each password consists of 10 digits, each of which can be any number from 0 to 9. There are 2 kinds of passwords that the game will accept, which I’ll call “regular” and “special” passwords. Special passwords are specific sets of 10 digits that the game looks for and reacts to in a unique way when they are entered. The complete list of special passwords is as follows:

- 075 541 6113 – Busy signal sound 1

- 800 422 2602 – Busy signal sound 2

- 206 882 2040 – Busy signal sound 3

- 135 792 4680 – Play hidden circuit: “Another World Circuit” (must hold Select button and press A + B to accept password)

- 106 113 0120 – Shows credits (must hold Select button and press A + B to accept password)

- 007 373 5963 – Takes you to fight against Mike Tyson

The other kind of passwords that the game accepts are the regular passwords. Regular passwords are a coded representation of the progress that you’ve made in the game. The game data that is encoded into a regular password includes:

- Number of career wins

- Number of career losses

- Number of wins by knockout

- Next opponent to fight

Encoding Passwords

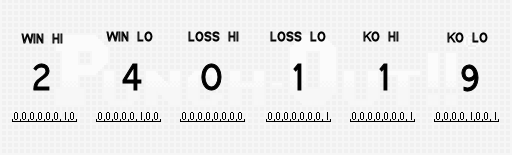

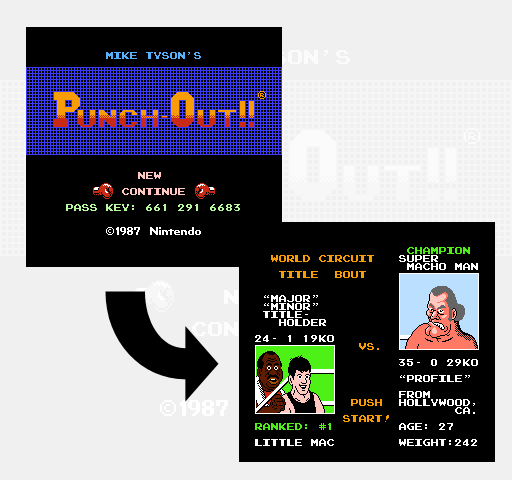

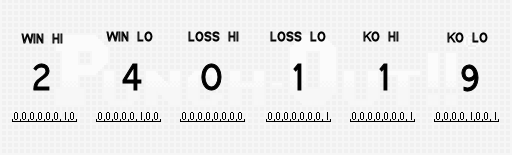

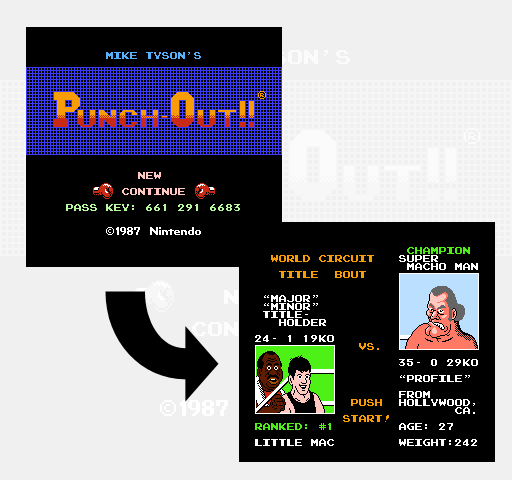

We’ll use an example game with 24 wins, 1 loss, 19 knockouts and starting at the world circuit title fight against Super Macho Man to see how passwords are generated.

The process of encoding this game state into a password begins by collecting your number of wins, losses and KOs into a buffer. The game represents each number in binary-coded decimal form with 8 bits per digit and 2 digits for each value. So for our 24 wins, that’s one byte with the value 2, and a second byte with the value 4. Then comes the pair of bytes for the number of losses and one more pair for KOs for a total of 6 bytes of data. The diagram below shows these 6 bytes with their values in both decimal and binary on the bottom.

The next step is to generate a checksum over those 6 bytes. The checksum byte is calculated by adding the 6 individual bytes together and then subtracting the result from 255. In our case we have 2 + 4 + 0 + 1 + 1 + 9 = 17 and then 255 – 17 = 238.

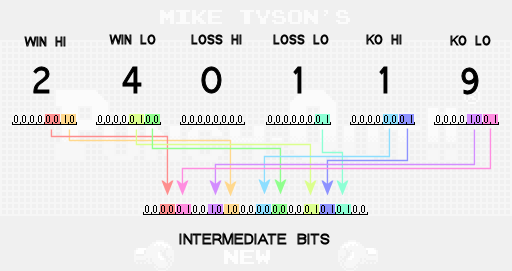

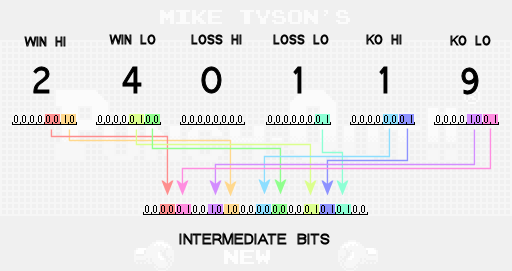

Next we shuffle some of the bits from the 6 bytes into a new buffer. We can think of the new buffer as a single 28-bit intermediate value that we’ll begin to fill in piece by piece. The bits from the first buffer are split into groups of 2 and moved around to different hard coded positions in the second. This is the first of a few steps whose sole job is to obfuscate the data make it difficult for players to see how passwords are generated.

Notice that not all of the bits from the original buffer are transferred into the new intermediate buffer. These bits are ignored because they are known to always be 0. Your number of losses in particular only needs to contribute 2 bits of information to the password because of the rules of the game. If your total number of losses ever gets up to 3, you’ll get a game over and never get a password. Therefore, you only need to be able to represent the numbers 0, 1 and 2 for your number of losses and that requires only 2 bits.

Next we shuffle more bit pairs into the intermediate buffer. The first four pairs come from the checksum value that we computed earlier. The other pair of bits comes from the opponent value. The opponent value is a number that tells which opponent you’re going to fight next after you enter your password. There are three possible opponent values that can be used:

0 – DON FLAMENCO (first fight of major circuit)

1 – PISTON HONDA (first fight of world circuit)

2 – SUPER MACHO MAN (last fight of world circuit)

Since we wanted to generate a password that puts us at Super Macho Man, we’ll use 2 for our opponent value. The checksum and opponent value bits are then shuffled into the intermediate bits as follows:

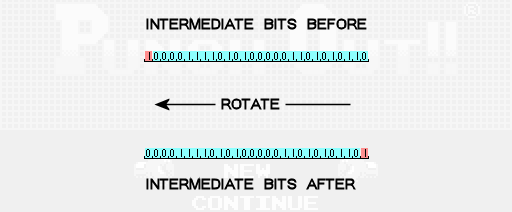

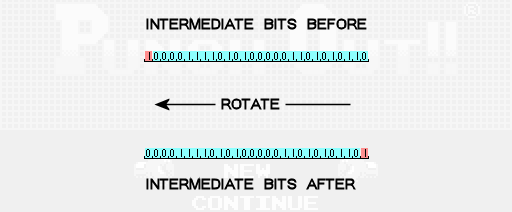

The next step is to perform some number of rotations to the left on the intermediate bits. A single leftward rotation means that all of the bits move one place to the left, and the bit that used to be the leftmost bit rotates all the way around to become the new rightmost bit. To calculate the number of times we’ll rotate the bits to the left, we take the sum of the opponent value and our number of losses, add 1, and take the remainder of that result divided by 3. In our case we have 2 + 1 + 1 = 4. Then the remainder of 4/3 is 1 so we’ll rotate the intermediate bits to the left 1 time.

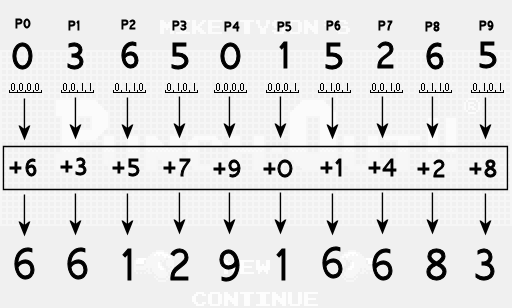

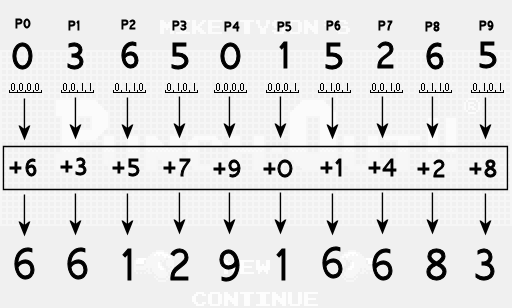

At this point the intermediate bits are thoroughly scrambled and now it’s time to start breaking them apart to come up with the digits that make up our password. Passwords need 10 digits so we’re going to break our 28 intermediate bits into 10 separate numbers that we’ll call password values P0, P1, P2, etc. The first nine password values will get 3 bits of data each, with the final value getting just 1 of the intermediate bits. To round out the final password value, we will also include bits that represent the number of rotations we performed in the previous step.

Finally we add a unique hard coded offset to the password value in each position. The final password digit is then the remainder of that sum divided by 10. For example in the seventh position we use an offset of 1, so we have 5 + 1 = 6, and then the final digit will be the remainder of 6/10 which is 6. In the fourth position the offset we use is 7, so we have 5 + 7 = 12, and then the final digit is the remainder of 12/10 which is 2.

Now we have the final password digits which we can try out in the game.

Decoding Passwords

The process of decoding a password back into the numbers of wins/losses/KOs and the opponent value is a straight forward reversal of all the steps outlined above and is left as an exercise for the reader. There are two notable mistakes however that the game makes when decoding and verifying player supplied passwords.

The first mistake happens in the very first step of decoding a password which would be to subtract out the offsets to get back to the password values. The original password values contained 3 bits of data each, which means their values before the offsets were applied must have all been in the range 0-7. However, a player might supply a password that results in a password value of 8 or 9 after the offset is subtracted out (modulo 10.) Instead of rejecting such a password immediately, the game fails to check for this case and instead allows the extra bit of data in the password value to pollute the collection of intermediate bits in such a way that passwords are no longer unique. Because certain intermediate bits could have either been set by the password digit that they correspond to OR the extra bit of a neighboring password value, there are multiple passwords that can now map back to the same set of intermediate bits. This is why you can find different passwords that give you the same in-game result, where as they would have been unique otherwise.

The second mistake is a bug in the logic the game uses to try to validate the data after decoding the password. The conditions that the game tries to enforce are:

- checksum that is stored in the password matches what the checksum should be given the win/loss/KO record stored in the password

- loss value is 0, 1 or 2

- opponent value is 0, 1, or 2

- rotate count stored in the password is the correct rotate count given the loss value and opponent value that were stored in the password

- all digits of win/loss/KO record stored in the password are in the range 0-9

- wins is >= 3

- wins is >= KOs

If any of these conditions are not met, the game intended to reject the password. However, there is a bug in the implementation of the final check (specifically when comparing BCD encoded numbers.) Instead of actually checking for wins >= KOs, the game will allow cases where the hi digit of wins is 0, the lo digit of wins is >= 3 and the hi digit of KOs is less than the lo digit of wins. For example, a record of 3 wins, 0 losses and 23 KOs will be accepted by the game (as demonstrated by the password 099 837 5823) when this was intended to be rejected (since you can’t have won 23 fights by knockout if you’ve only won 3 fights total.)

Conclusion

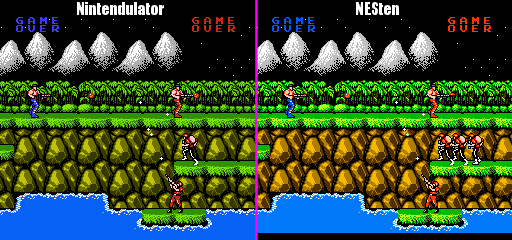

The particular details of this encoding scheme are unique to Punch-Out, but the general idea of taking some important bits of game state, transforming them in a reversible way to obfuscate their relationship to the original game state, and then using them to generate some number of symbols to show to the player as a password is fairly universal. Checksums can be used to make sure that accidental random changes to the password (if your finger slips while entering it) are most likely to result in an invalid password instead of some other password representing a random other game state.

If you’d like to offer feedback or keep track of when new posts in this series become available, you can follow me on twitter @allan_blomquist

(This is part 1 of a series – Next)

Human Resource Machine is a puzzle game for nerds. Use your little workers to solve each level’s puzzle, and get promoted up to the next floor. Repeat. Each level is one year.

Human Resource Machine is a puzzle game for nerds. Use your little workers to solve each level’s puzzle, and get promoted up to the next floor. Repeat. Each level is one year.